Strong State Capacity is a product of blurred lines

Beyond "Good Enough for Government Work": What Japan and Irvine, California Teach Us About How to Build For the Long Term

So last article I talked about how governments around the world fared during Covid and the two “products” they needed to sell in order to weather the storm. I wrote it because any good Product person doesn’t just care about shipping the first version of something, but building something that is trusted, that can adapt with the times, and can be built to last.

I ended up down that rabbit hole by another completely unrelated topic - The Russo-Japanese War of 1905. Don’t worry, this isn’t my Roman Empire or something, but a while ago I was performing my duty as a tech bro by listening to the Dwarkesh Patel podcast where a recurring (and freaking fantastic!) guest, Sarah Paine, was back to talk to everyone through a lecture on early 20th-century Russian/Japanese conflicts.

She does such a great job with these because she makes me feel way less like a pompous humanities douche and more like someone who just wants to know things for the sake of knowing things. Because its good (and fun) to know things.

Anyway, a big part of that lecture covers the Russo-Japanese War, its origins, outcomes, and why it ended the way it did. She’s quick to admit she might not have all the answers, but she offers strong evidentiary reasons for historical events. A very small (like 45 seconds) piece of the lecture touches on how both nations financed their ships, railroads, and military campaigns. She explains here that Japan’s war loans came from private Western institutions, with interest rates tied to their military performance. She moved on, but I thought, “wait....hold up. You can’t just say that and move on like it’s totally normal.” She can, obviously, since this is her lecture, but...I can press Pause just as easily 😛

Now, we could go into a lot of different directions with today’s post, but I’m going to constrain it to three things:

How did Tsarist Russia and Japan go about building their war-fighting “products” for the conflict?

How did State Capacity (the government’s ability to make, run, and do things) in either situation factor in?

How should we think about State Capacity in the US today? (Spoiler: It’s not a war-fighting example)

Russian Railroads!

The Russian Empire, much like Russia today, relied heavily on railroad infrastructure. Most of this was in the western parts of the country, with less in the east near Japan. However, that was starting to change with the Trans-Siberian Railway, but its last stretch wasn’t even finished until the very end of the Russo-Japanese War—a key factor in the war’s outcome.

Despite significant internal taxation, it wasn’t enough. By 1900, Russia was the largest foreign debt holder in the world

Their naval fleet was largely supplied by the French (who were allies, both aiming to contain Germany).

How could the Russian Empire pay for this?

(This is a worthwhile tangent, but if you don’t care feel free to skip this part.)

They lacked the internal capacity to finance their naval fleet, railroads, and other major infrastructure. So, they borrowed. A lot. From the French people.

Despite significant internal taxation, it wasn’t enough. By 1900, Russia was the largest foreign debt holder in the world, with French investors owning 80% of foreign government debt. This heavily influenced both buying decisions and geopolitical alliances. The Russians wanted State Capacity (a phrase we’ll focus on today) to do a lot of heavy lifting. They’d do design and technology transfers to build things in-house at the government’s direction and control and culturally, it was important to have that centralized control. To be clear, this isn’t good or bad in and of itself and it’s a theme we’ll focus on today.

So with all the borrowing from Europe, it’s no wonder that most of the Russian Navy were essentially vessels supplied by or the licensed designs of the other European nations and a secret purchase of a submarine from the US. Russian debt products were issued by in French, German and Dutch capital markets. With all this money and sourced componentry, they spent a lot of effort to industrialize the western parts. While the leaders at the top were a little wonky, a big part of all this Capex was under the stewardship of Sergei Witte, the finance minister at the time. He’s a whole writeup on his own and I can’t put y’all through another tangent so let’s move on to Japan.

Japan’s the Underdog

Like we talked about last week, a nation’s long-term sovereign debt (government bonds) is its most essential product—a promise to pay future investors, whose valuation is the market’s real-time assessment of national trust. Its serviceability depends on reliable revenue and a sensible budget. Sounds simple, but history (and today) shows countless examples where this fails. Japan offers a fascinating case of self-reinvention.

Japan saw what happened to China and realized they needed to avoid that outcome at all costs.

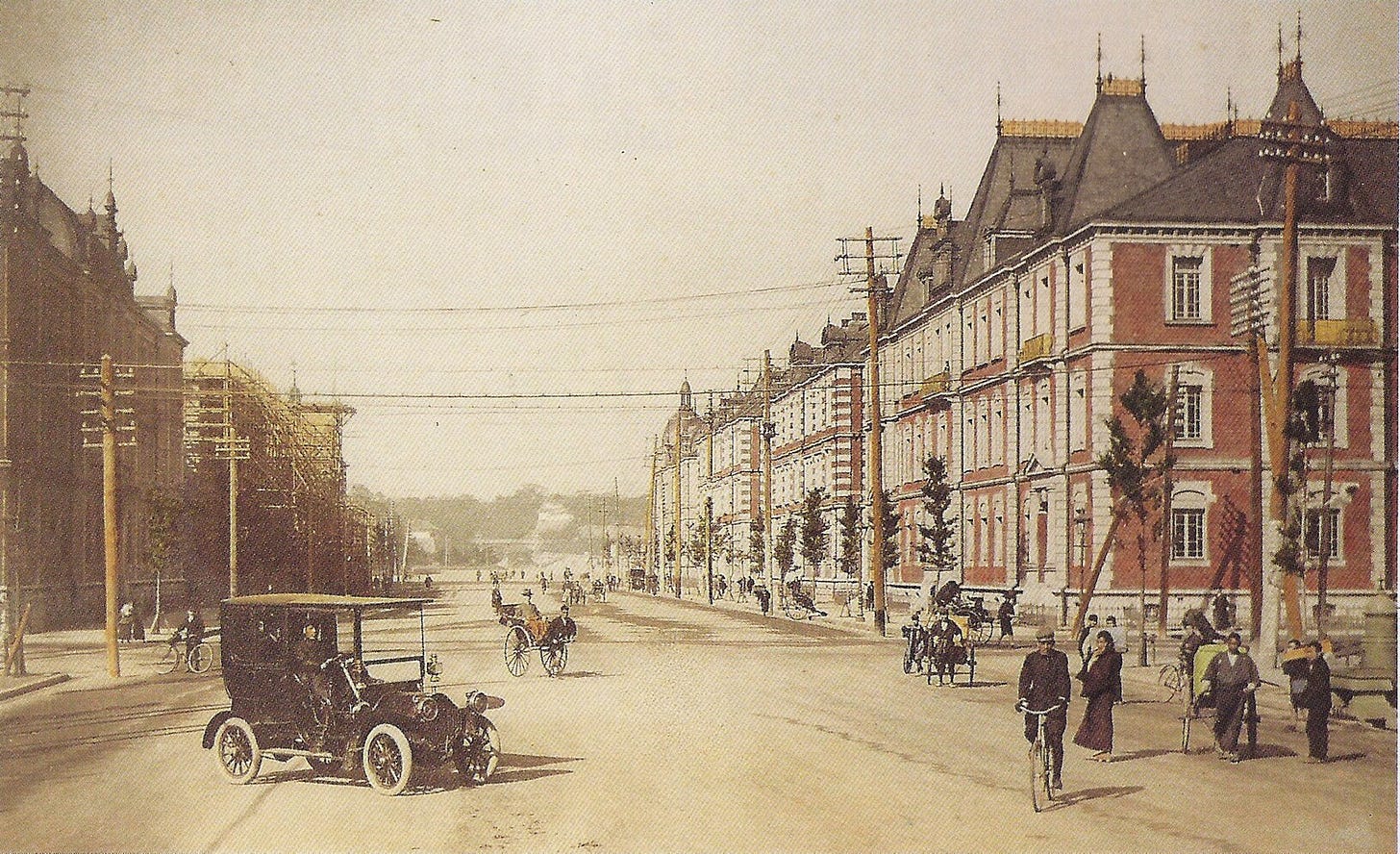

In the late 1800s, a big thing that started to happen around this time was the Meiji Reformation. I intellectually knew about how Japan changed it’s government to govern more similar to Western institutions (thank you bill wurtz), but things were not that easily accepted within Japan. There was a huge cultural resistance to selling “western institutions” to the Japanese people UNTIL this war broke out and Japan started to get some wins.

Japan saw what happened to China and realized they needed to avoid that outcome at all costs. (We’ll conveniently ignore the first Sino-Japanese War that happened a few years earlier) So they just outsourced everything to start with. This is a very different approach to State Capacity than the Russian Empire. Japan didn’t pretend that it could grow its industrial capacity overnight. So they went out and bought literally the best of the best war-fighting products for their Navy, mostly from the British and the Italians. They then spent the following years building out their domestic capacity, but that wasn’t their main objective. So now everyone’s got their fancy ships and trains. Time for war, I guess?

The War That Re-Rated the Financial Products

So a lot of stuff went down during the event, but the Russo-Japanese War served as a brutal market stress test for the sovereign debt products of both empires. At the end, it was a dramatic Re-Rating of their bond value by external investors.

Tsarist Russia’s Downgrade: Despite its larger economy, military defeats and rising social unrest (especially the 1905 Revolution) exposed Russia’s fragile institutional structure. The social risk became a financial liability. Investors realized the state’s internal capacity to manage crisis was low. The value of Russian debt fell because the underlying product was too unstable. They then had to borrow even more from France just to fulfill their existing debt burden, which was already rather high.

Meiji Japan’s Upgrade: Japan, despite its smaller initial reserves, executed the war with really good fiscal and military discipline. Its ability to manage logistics, fight effectively, and impose new taxes proved its execution capacity was high. Its product was quickly upgraded by American and British financiers, allowing it to raise the critical foreign capital needed to finish the war.

While the war ended with objectives achieved before Russia could fully deploy troops via the Trans-Siberian Railway, the lesson is clear: The financial value of an organization—be it a company’s stock or a country’s bond—is determined not just by its size, but by everyone’s perception of its internal capacity to execute under stress. This is pretty helpful context to keep in mind for life in general.

Diving into State Capacity

We’ve talked a lot about financial engineering on this blog. While it’s commonly associated with how Private Equity funds do “Value Creation,” it can swing the other way, too. In the West, we often view State Capacity with disdain; it’s a punch line I’ve used countless times when something was “good enough for government work.”

Meiji Japan, however, was different. Its approach was much like the industrial policy-making seen in China today and South Korea decades ago.

The government actively invested in establishing and operating industries vital for modernization, known as “model factories” (kan’ei kōjō). Similar to Tsarist Russia, this involved technology transfers. After purchasing the “best of the best” products globally, Japan aimed to build its own capacity for maintenance and repair. The purpose was to introduce Western technology and best practices. These transfers included shipbuilding, railways, telegraphs, and advanced textiles. These choices stemmed from a clear nationalistic mission that transcended private interests—a condition that no longer exists in that extreme form today, but which we can learn from. Once stable, the government typically sold their assets in these industries to wealthy private businessmen at low prices.

Many of those companies still exist over a century later, like the Mitsubishi Corporation. While private, these companies act very differently from their American, British, or Russian counterparts. They weren’t just an excuse for individuals to amass wealth by acquiring conglomerates cheaply from the State; they were a product of national development. Times are different, especially globally, but there’s a clear yearning for domestic or localized priorities in many parts of the West again. The real lesson here is about what matters most to the nation as a whole, and how best to ensure citizens get the best outcomes. Not everything is deterministically good or bad and the sheer contrast between Japan’s approach to Tsarist Russia shows that. Before I dive deeper into this, I want to offer a completely different, and surprisingly rare, example from the United States.

Blurring the lines between government and private entities

So here’s the counter argument: what matters most is the willingness to accomplish difficult or complicated things. We often hear that the profit motive makes private enterprises more efficient than governments, but I don’t think that’s always the case. We’ve all seen bloat, process as a proxy for the obvious, and political silos hinder progress in most private enterprises from startups to large corporations. So, is there an example of something that side-steps this whole debate, not only works well, but has endured for a really long time?

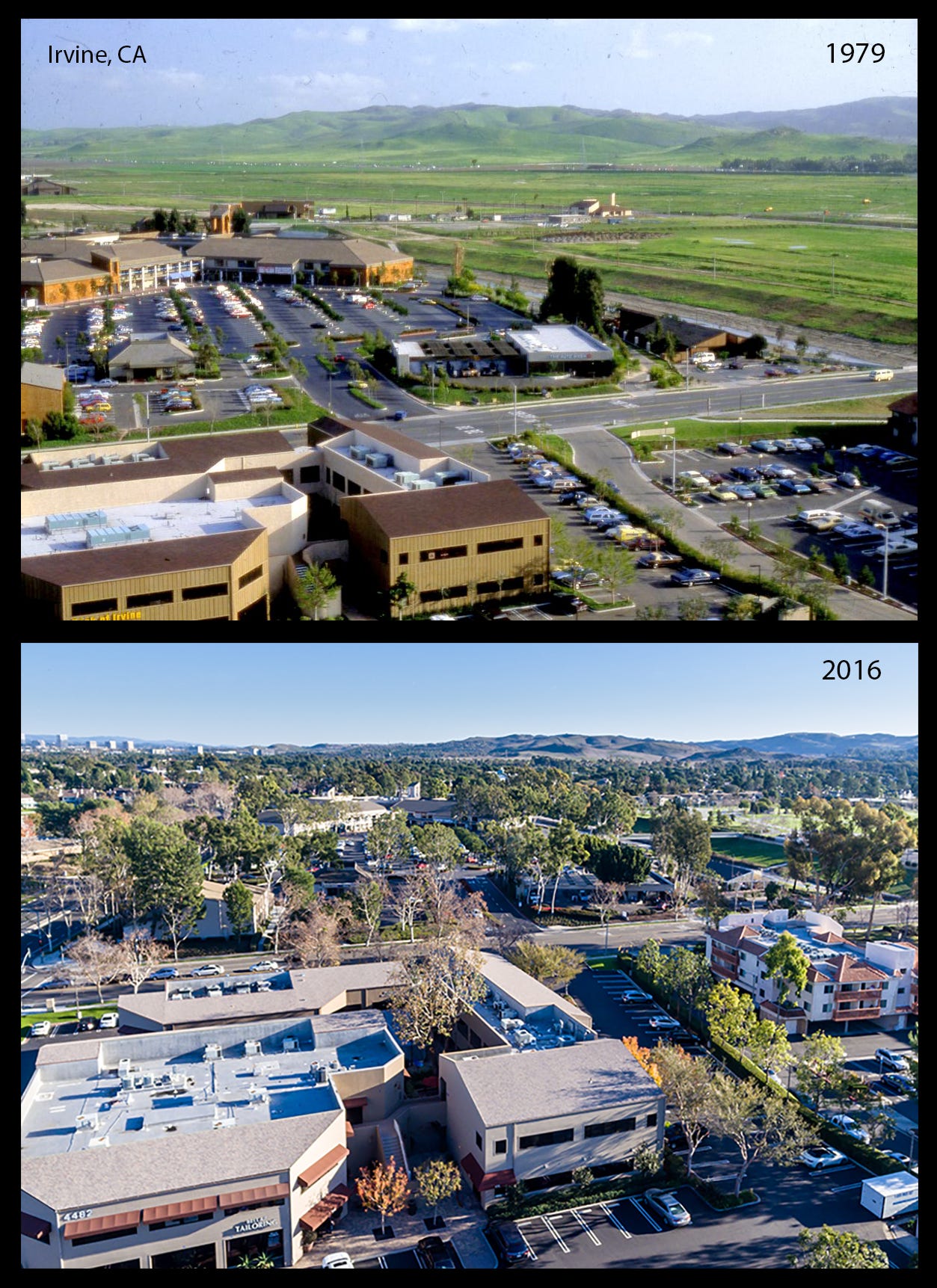

Turns out, my hometown of Irvine, California, is a pretty rare bird. It’s one of those unique planned cities in the U.S. that was mostly privately developed, yet with a cohesive, village-oriented design and a municipal structure that’s really worth thinking about.

This ad from the 1980s is hilarious to me.

For a long time, The Irvine Company essentially was the planning authority, controlling nearly all the land. This is where a “state capacity” mindset gets applied by a private entity: deciding where to place parks (most homes are within a ten-minute walk!), and ensuring development was self-financed. Roads, sewage, schools – much of it paid for by capturing the increase in land value that resulted from its own investment and planning.

Even though Irvine is a fully functional municipality with a mayor and city council, The Irvine Company remains the most powerful actor. It’s the largest taxpayer and landowner, owning huge portions of commercial centers and acting as the city’s private infrastructure arm for major growth. This structure means the city itself needs to put up less capital.

Growth is a collective agreement, and The Irvine Company understands you can’t just build for a quick buck; enduring value, brand, and sustainable infrastructure are key to the long-term appreciation of homes.

Of course, there’s tension, especially with longtime residents wanting more control. Yet, The Irvine Company has largely proven it can meet the needs of those who rely on it, whether customers, employees, or institutions. This blurred line between private entity and government body is fascinating. It offers a healthy alternative to the often unnecessarily bifurcated U.S. debate about what governments are good for versus what private companies should do.

The proof is in the pudding: Irvine has been financially self-sufficient for most of its history, and residents enjoy some of the best public schools in the country. This all stems from a village model that sustainably offers homes and the corresponding services people actually want – like a nearby shopping center, school, or community center you could theoretically bike or walk to. (Though, let’s be real, unless you’re retired or a kid, no one’s really walking that much in Irvine!)