Product Lessons: How Nations Financed during COVID

Everything is a Product (even National Debt!)

We live in a world where our coworkers (temporary or permanent) can be from anywhere in the world. This is true for sectors like agriculture and automotive manufacturing just as it is for tech. Understanding how their home countries deal with crises gives us a way to connect with them, but also a keen understanding of how they may culturally view risks, tradeoffs, and eventually make decisions in a room with you when you’re building, buying or selling a product. So we’re going to continue to take a detour from AI hype and focus on how countries sell sovereign products, through the lens of the global Covid crisis.

NOTE: I wanted to make it clear that a ton of important people and decisions had to be in place for us to weather the Covid crisis. My wife is in healthcare and when we were in the Bay Area in California, she had a pretty up close look at the harsh realities of Covid with her geriatric patient population.

Today, however, we’re going to look at a very macroeconomic thing and we’re going to compare how the US dealt with it and compare it to India, China, and Kenya. Each of these nations offer us a different approach to weather the storm, and it’s always helpful to see what we can learn from it.

These nations represent very different aspects of human experience around the world. Going into 2020, they all had different tools and levels of maturity in their economies to deal with Covid. For the US, this was something they hadn’t dealt with in a century. For Kenya and India, this was a real test of their ability to deal with a non-military crisis that affected their entire nation. We’re not going to use any country as a benchmark since no one really got everything right and there are lessons to learn all around.

Sovereign Financing 101

Before we dissect how each country handled the economic fallout, let’s cover the basics: how governments actually get their hands on money when they need it. Remember my mantra, “Everything is a product to someone”? Well, even a nation’s need for capital is a product, meticulously designed and sold.

When we talk about how countries financed their COVID-19 responses, we’re really talking about how effectively they designed and “sold” these financial products, and who was willing to buy them.

When a country needs to raise serious cash – whether for infrastructure, social programs, or, say, a global pandemic – it essentially sells two main “products” in this market: sovereign bonds and syndicated loans.

They break down a bit differently:

Sovereign Bonds: This is like a country issuing notes to thousands of investors around the world similar to your local city or state doing the same thing. Private investment banks step in as the intermediaries. They act as underwriters (buying the bonds from the government, guaranteeing the capital, then reselling them), advisors (telling the government when and how to sell), and marketers (using their global networks to find buyers). It’s a complex dance, but it’s how governments tap into that vast global pool of money. And by the way, this has been going on forever, its not some new thing.

Syndicated Loans: Sometimes, a single bank can’t lend enough, or the risk is too high for one institution. That’s when a group of banks pools its resources to offer a giant loan to a nation. One or more banks act as the lead arranger to do the paperwork and coordinating activities, inviting other folks to join the “syndicate.” This is particularly common for developing countries or emerging markets that might not have easy access to the big bond markets. Why? The trust isn’t there. This is going to be a recurring theme today.

So, when we talk about how countries financed their COVID-19 responses, we’re really talking about how effectively they designed and “sold” these financial products, and who was willing to buy them.

The Pre-COVID Starting Line

Going into 2020, our four contenders weren’t all starting from the same place. Each had a unique financial “tool kit” and a different level of economic maturity.

The United States: Wielded the the global reserve currency. This meant its deep capital markets could tap into demand from literally the entire world.

India: Boasted a massive domestic savings pool and a growing, but still maturing, financial market. It largely relied on its own internal strength.

China: Operated with a highly state-controlled financial system, immense national savings, and strict capital controls, giving the government significant direct leverage.

Kenya: Faced significant external reliance, a much smaller domestic capacity to absorb debt, and a heavy pre-existing debt load, severely limiting its policy options.

Weathering the Storm

Now, let’s see how these different starting positions and financial strategies played out when the pandemic hit.

The United States: The Global Reserve Currency Advantage

The U.S. didn’t just weather the COVID-19 storm; it played a completely different game, leveraging its unique superpower: the global reserve currency.

Unlike many other nations, the U.S. fiscal response was defined by massive, direct cash injections straight into the pockets of its citizens and businesses. Most working-age Americans know about this, so this will for the younger audience and the non-Americans.

We’re talking:

Stimulus Checks: Direct payments sent to most Americans.

Enhanced Unemployment Benefits: A significant weekly boost to unemployment insurance.

Paycheck Protection Program (PPP): Forgivable loans designed to keep small businesses afloat and employees on payroll.

The goal was clear: there was no time to be thoughtful, just pump money directly into people’s and companies’ pockets and keep the economy from seizing up.

A Flood of New Money Comes In

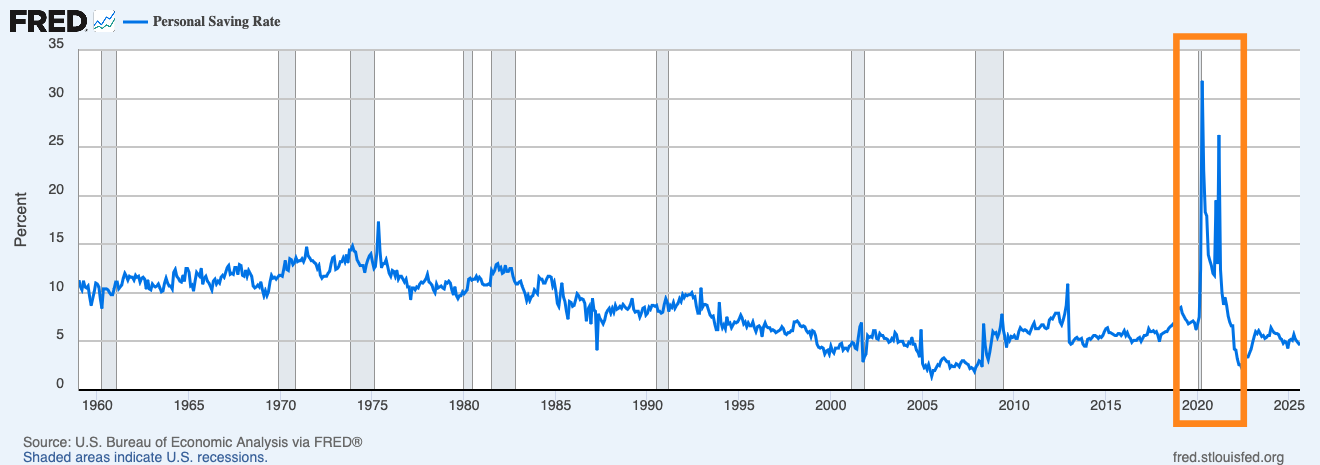

This direct injection had a fascinating effect on household savings. Like in India, consumption opportunities vanished during lockdowns, leading to “forced savings.” But crucially, in the U.S., household disposable income actually increased for many, especially in lower and middle-income brackets, thanks to all that government cash. This created a massive glut of new money, but the bigger problem was the absolute lack of cultural norms for building up savings.

And what did Americans do with it? Much of it went into bank deposits, sure. But we also saw an unprecedented and speculative retail investor boom. With zero-commission trading apps and time on their hands, many dove into the stock market, famously fueling the “meme stock” phenomenon (think GameStop, AMC, etc). Others poured money into crypto. For those stuck at home, it was less about conservative saving and more about actively chasing returns.

Because the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency, foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and international investors have a structural, almost mandatory, need to hold dollar-denominated assets, primarily U.S. Treasuries.

Debt Absorption: The Fed and The World

This is where the U.S. truly stands apart. The massive issuance of U.S. Treasury bonds wasn’t just absorbed by its own citizens; it was absorbed by a diverse global audience, supercharged by the Federal Reserve. Because the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency, foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and international investors have a structural, almost mandatory, need to hold dollar-denominated assets, primarily U.S. Treasuries. The U.S. effectively outsourced a large part of its crisis financing to the global system – a phenomenon people refer to as the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege.“

India: Self-Reliance and Accidental Savings

If the U.S. leveraged its global financial superpower, India’s story is one of resilience and the quiet strength of a nation that largely borrows from itself. There were no “shock and awe” direct payments on the same scale; instead, India relied on its vast domestic savings pool and a robust financial system to absorb an unprecedented surge in government borrowing. I want to remind people that Covid’s Delta variant hit India hard. There isn’t a person anywhere in India or a friend/family member around the world who didn’t see someone close to them get hit or unfortunately pass away from Covid during this time.

India’s fiscal response was more focused on providing a safety net and supporting vulnerable populations rather than direct, broad-based income replacement. Think:

Free staple grains for the poor.

Credit guarantees for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to keep them from collapsing.

Some smaller, targeted cash transfers to vulnerable parts of the population. The goal was to cushion the immediate blow and prevent widespread destitution

Now, here’s where it gets interesting, and it’s a story many of us might miss if we just look at headlines. While the average Indian citizen didn’t suddenly start buying government bonds in droves, household savings did skyrocket. Net financial savings of Indian households surged to a multi-decade high of 11.5% of GDP in the 2020-21 fiscal year.

Iit was a direct and rational response to the crisis:

Forced Savings: During severe lockdowns, people simply couldn’t spend money. Malls, restaurants, travel – all shut down. Income that would normally be spent had nowhere to go and accumulated in bank accounts.

Precautionary Savings: The pandemic brought immense uncertainty about future jobs, income, and health. Fear of the unknown prompted families to save aggressively as a buffer against future shocks.

A portion of these savings also flowed into mutual funds, particularly debt funds, which are significant institutional investors in government bonds. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) was a crucial stabilizing force. Their bond-buying programs (OMO, G-SAP, and a couple of others that I can’t immediately remember) injected liquidity and stabilized yields, preventing a market collapse.

So, while it felt like the country was “borrowing against itself,” it was actually the collective, crisis-driven decision to save that temporarily swelled the national savings pool.

The government didn’t (and honestly, couldn’t) simply force banks to absorb all the new debt via high Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR) mandates. The absorption during COVID-19 was a true market response kind of by accident, but channeled efficiently by a robust domestic financial system.

India’s experience demonstrated the immense strategic advantage of a high domestic savings rate and its ability to self-finance even in the face of an unprecedented crisis.

Turns out, a nation’s most powerful financial tool isn’t always a fancy global mechanism, but the accidental, collective prudence of its own people, born purely out of necessity.

The problem in place right now is that there is a lot more borrowing activity than ever before in India, coming out of the pandemic. Much like the US isn’t used to saving well, non-agricultural parts of India aren’t really used to being stewards of revolving credit or larger forms of debt while sustaining limited savings. But...that’s a whole post on its own :P

China: The State-Directed Production Machine

If the U.S. was about stimulating demand and India about leveraging domestic savings, China’s response was a heavy focus on state-directed production. By now, you can see how cultural bias is turning up in these policy choices. It wasn’t about giving money directly to citizens or relying on organic market forces; it was about the state’s absolute power to get factories humming, infrastructure built, and the economy roaring back through sheer force of will.

China’s fiscal stimulus was almost the mirror image of the U.S. There were no large direct cash handouts to citizens. Instead, the focus was heavily weighted towards the supply side as soon as the first “Zero Covid” shutdowns turned off (and before the next wave of shutdowns came in):

Tax Cuts and Fee Reductions: Businesses, especially manufacturers, received significant relief.

Massive Infrastructure Spending: The government explicitly ordered state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to accelerate projects like high-speed rail, 5G networks, and energy grids. The aim was to create jobs and maintain production capacity.

State-Directed Lending: Financial institutions were guided to lend to corporations to ensure they didn’t collapse, keeping the industrial engine running.

The philosophy is pretty clear: control the virus, then stimulate production. Keep the factories open and people employed, and the economy will recover through exports and investment.

China already boasts one of the world’s highest household savings rates, partly due to a less robust social safety net. The pandemic didn’t just amplify this; it created a unique psychological dynamic. The strict, sudden, and often unpredictable “Zero-COVID” lockdowns meant families saved by default. Imagine not knowing if your city would be the next to shut down for months, cutting off income and access to essentials. We’re not going to go into it today, but much of Chinese household wealth was tied up in real estate and that was just turning into a huge issue for them. The result was a population that, despite an economy focused on production, was hoarding cash, unsure of what the next lockdown might bring.

When China needed to borrow big, their state-controlled system basically just funded itself.

Think of it as a super-efficient, almost circular flow: the government issued debt, and then their massive state-owned banks, like ICBC or Bank of China, were simply told to buy it up (this is what India didn’t do, by the way). The central bank (the PBoC) made sure those banks had plenty of cash, and strict capital controls kept money from escaping the country. Whether you like it or not, it is kind of crazy they could get away with the last bit. With nowhere else for all that domestic savings to go, the government always had eager buyers for its bonds. (Side note: Starting this year, looks like China is starting to ease up a little bit on its capital controls, so that’s gonna be pretty interesting to watch)

In summary, China’s pandemic response was a testament to their power of absolute state control. It used its command over production, its financial institutions, and its citizens’ savings (both voluntary and involuntary) to orchestrate a recovery focused on supply, all within a tightly managed, largely closed financial loop. But you’ll be left with a population in constant fear of whether they can walk out of their home next week or not, and that’s not fun. It’s a stark contrast to the market-driven approaches of the West, offering its own unique lessons in crisis management.

Kenya: Crisis Management Under Acute Constraint

Forget economic philosophies for a moment. If the U.S. and China had big strategic choices, Kenya’s pandemic experience was pure crisis management under extreme pressure.

They were caught in a desperate balancing act: battling a public health emergency and trying to stave off a sovereign debt crisis all at once. Their options were incredibly limited, which meant relying heavily on international financial institutions just to keep going.

While wealthier nations debated spending trillions, Kenya was hit by a brutal “fiscal scissor”: government revenues collapsed just as spending needs soared. Tourism and horticultural exports were decimated by global lockdowns and disrupted supply chains. This left the government with dramatically less money.

Kenya’s stimulus was a mere fraction of the size of the other nations we’ve discussed, focusing on immediate, critical relief:

Temporary tax relief (e.g., reductions in VAT and income tax for lower earners).

Modest cash disbursements to the elderly and most vulnerable populations.

Some credit guarantees for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to prevent a total economic collapse.

Emergency healthcare spending to bolster a struggling medical system. There were no massive direct checks or grand infrastructure projects. The government simply lacked the fiscal capacity. The primary goal was to cushion the immediate blow and keep the lights on, not to stimulate a roaring recovery.

M-Pesa to the rescue…sort of

Unfortunately, while households in developed nations and even India saw savings rates spike, the vast majority of the Kenyan population experienced the opposite: For millions, especially those working in the informal economy (street vendors, casual laborers, small-scale traders), lockdowns meant a complete loss of income. They were forced to draw down on whatever meager savings they had accumulated, simply to survive day-to-day. M-Pesa, a fantastic mobile money platform, became a bigger piece of national infrastructure. The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) waived fees on small mobile money transactions, which proved invaluable. This made it super easy for people to send aid to each other, like relatives in the city sending money back to their villages. It also meant folks could pay digitally since cash was too risky to handle. Though the middle class and up were in a better spot with savings, the story of the Kenyan household was one of hardship, resilience, and reliance on community and family support.

And when you take things to the national level, it gets really easy to see how difficult the decisions are to make. Kenya does have a domestic bond market, and local pension funds and banks do buy government debt denominated in Kenyan Shillings. However, this market is nowhere near large enough to absorb the kind of deficit the crisis created. Attempting to do so would have sent domestic interest rates soaring, crushing the economy.

Lifelines were a matter of life and death

Kenya simply couldn’t self-finance its way out. Their most critical calls went to Washington D.C., securing emergency financing from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Getting an IMF program wasn’t just about the cash; it was a vital signal of confidence to all other international creditors, essentially saying, “Kenya’s taking the necessary steps, they’re not about to default.” It was a true lifeline. On top of that, Kenya got a temporary break from paying some debts through the G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), freeing up crucial cash. Trying to borrow from private international markets (like issuing new Eurobonds) was just too expensive and risky, with interest rates that would have crushed the struggling nation.

In conclusion, Kenya’s experience starkly illustrates the profound inequalities of the global financial architecture. It lacked the monetary sovereignty of the U.S. and Japan, the state-directed capacity of China, and the vast domestic savings pool of India. Its response was a testament to navigating a global storm with limited tools, where every policy decision was a difficult trade-off, and survival depended heavily on the support and confidence of the international financial community.

We are way past “normal,” but aren’t doing much about it

We see how nations, from global superpowers to emerging economies, navigate unprecedented crisis. But this isn’t just a history lesson for economists. It’s a stark mirror reflecting the strategic choices we, as product builders, engineers, and executives, face every day in our companies – especially now, as the illusion of a stable “normal” has been shattered.

The true “boring” takeaway here—the one that really matters—is about trust as the ultimate accelerant for value creation, and why we must now pivot from optimizing for a past stability to building for an uncertain future.

Trust is Your Ultimate Capital for Big Ambitions

Looking at these national stories, it’s clear: trust isn’t just a bonus; it’s the core ingredient that lets you do big, ambitious things. The U.S. relies on global trust in its currency. India taps into deep domestic trust in its financial system. Nations without that trust? They’re stuck paying exorbitant costs, with severely limited options, always playing defense. For companies, it’s the same deal. Consistently earning and keeping trust—from customers, employees, and investors—is what gives you the freedom to innovate, take smart risks, and really create value. Without it, you’re constantly battling headwinds, your choices are narrow, and every move is under the microscope.

Speedrunning to develop high-speed rail or a flashy infrastructure project for optics, without genuine underlying trust and capacity, is eerily similar to a legacy company rushing to be “AI-first” within a year, driven by hype rather than deep product conviction. It’s often a shortcut that bypasses the real work of building enduring value.

Financial Engineering was a Luxury

For decades, in a context of relative global peace and predictable societal structures, we had the luxury to pursue agendas heavily focused on financial engineering.

Companies could do things like EBITDA-optimization and margin expansion, often by cutting internal know-how, slowing expensive new feature development, and purging what seemed like “inefficiencies.” These decisions, while impacting internal capacity, felt acceptable because the core aspects of society— global supply chains, geopolitical stability, public health—were largely constant. Then came COVID-19, and that underlying stability vanished overnight. It wasn’t just a market blip; it was a non-militarized test of our ability to adapt to a radically changed environment. We largely kept things going as if we were going to snap back to “normal.” But as our national comparisons show—from Kenya’s precarious reliance to India’s internal fortitude—the world didn’t go back to normal. We’re still dealing with the aftermath. The structural vulnerabilities, previously masked by calm, were laid bare.

A Focus on Structural Resilience and Positive-Sum

So, if “normal” isn’t coming back, the next five years will present every company with its own “non-militarized test,” demanding a redefinition in a market that might irrationally expect unsustainable financial performance. This isn’t just about avoiding short-term stock bumps; it’s about recognizing that the luxury of pure financial engineering is over.

Anyone who takes their eye off the ball by fixating solely on cost controls, instead of pushing the upside through real value creation (and most importantly, communicating it well to the market on their own terms) is going to get a painful lesson. This means a re-focus on structural issues:

Investing in core product engineering: Building deep, internal know-how and capabilities, rather than externalizing problems or cutting crucial development.

Cultivating genuine trust: With employees (who hold that know-how), customers (who drive long-term revenue), and investors (who seek sustainable growth).

Building Antifragility: Designing systems and strategies that not only withstand shocks but benefit from disorder. We’ve talked about these items in the past. This is the path to creating a bigger pie for everyone. It’s about understanding that the big commercial picture now demands a focus on fixing our structural issues—both within our companies and in the broader economy—because the stable context that once allowed for less rigorous approaches is simply no longer guaranteed.

PS - I only mentioned AI like twice in this whole writeup because while it might be a potential driver for change, it is not a primary or monocausal driver for anything I am talking about.