Don't Optimize Everything

Originally posted on March 7th, 2025

The promise of something like A/B testing is seductive: data-driven decisions, optimized conversions, and a clear path to growth. But the reality is, most teams are doing it wrong. The core problem? Sample size. More specifically, how much sample size actually matters.

I found it surprising that the first (known) version of A/B testing started as a way to promote beer in the early 1900s? Schlitz Beer, out of Madison, Wisconsin, hired a man named Claude Hopkins to help grow the brand nationwide. It was pretty clever for its time - to test messaging and revenue attribution to marketing spend. It wasn’t perfect (I doubt the Don Draper types would utter the words “statistical significance” that often), but even they needed a mountain of data and information to make it work. And unless you’re in e-commerce or social media today, you probably don’t have that kind of user base to achieve said statistically significant results.

Let’s look at a small example of where optimization falls apart, and then a big one where it actually works.

Restaurant Email Campaigns

As I’ve mentioned before, I’m an investor in a restaurant. In general, it helps me have a pretty applied look at consumer behavior, price discovery, and microeconomics. We’ve been sending out weekly email marketing campaigns for about six months now. The workflows are mostly automated (except for the copy pasting, image uploads, and hitting “send”), and we’ve sent over 84,000 emails so far.

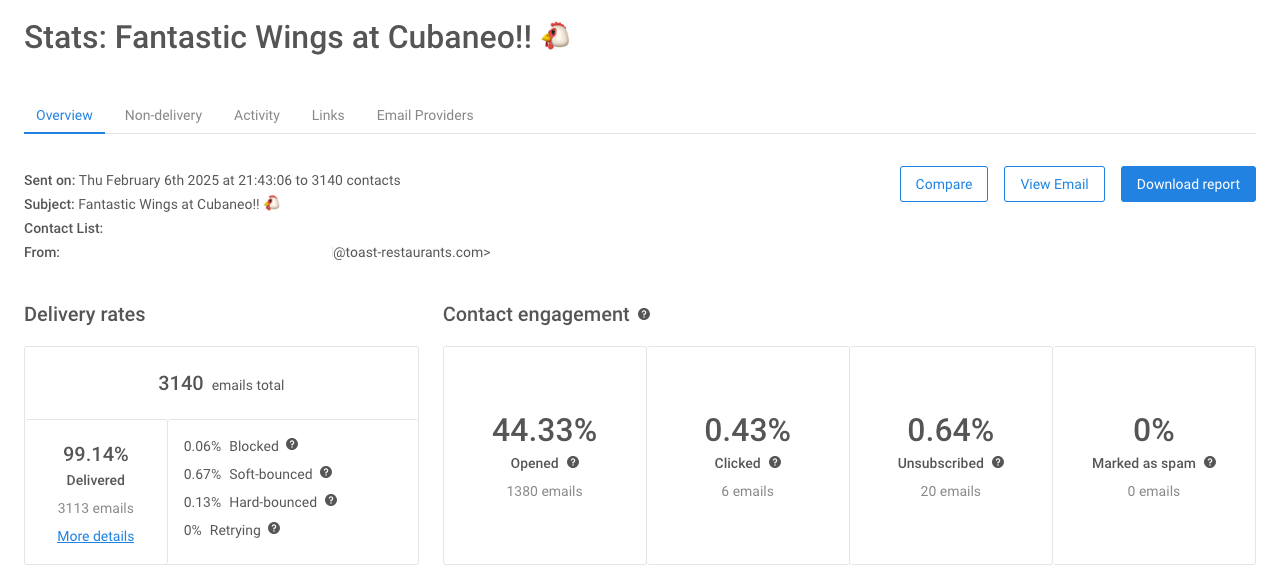

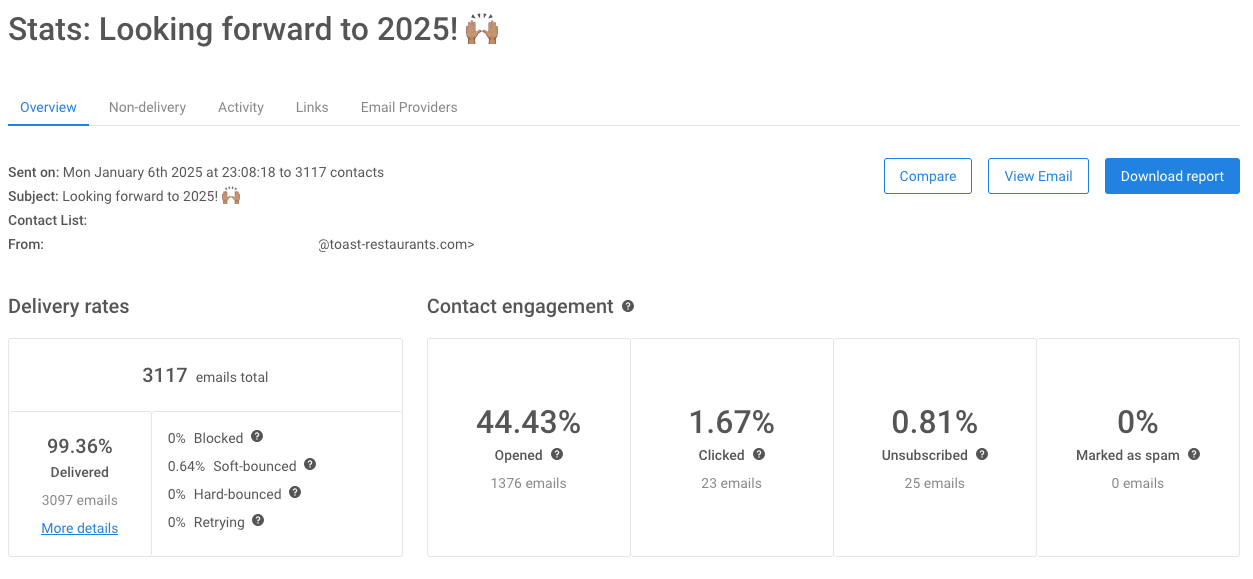

With that many emails, you’d think we’d have found some sort of causal relationship between what we promote, the CTAs we use, and the content itself. But nope, none whatsoever. Take a look at some of the campaigns below:

We send roughly 3000 emails each time and see about the same open rates. And yet, the sales attribution is all over the place. Just to double-check, I went back and looked at each campaign’s conversion funnel. The click-through rates (CTR) range from .5% to 2.3%, but there’s no causal link to sales performance.

Does it mean email marketing is a complete waste of time? Not at all. For us, it serves a very specific purpose: a weekly reminder to our patrons that we actually exist.

Here are two extreme examples:

The wings promotion, which brought in $2k in attributable sales, had a terrible CTR (.43%) and almost no downstream engagement.

The “Thank You” email, which generated just $10 in sales, had a decent CTR (1.67%) and even a few personal emails thanking us for improving the service.

To really nerd out, I ran an r-squared analysis across all 84,000 emails and couldn’t get a better result than .09 (technically, .088) relating open rates vs revenue per campaign. It was worse for CTR vs Revenue per campaign. For the record, those are terrible numbers.

Does it mean email marketing is a complete waste of time? Not at all. I mean, we could just be terrible marketers, but for us, it serves a very specific purpose: a weekly reminder to our patrons that we actually exist. It’s a recurring awareness campaign, a way to stay top-of-mind without breaking that social contract we’ve established. Customers might order online, book a table, or even just stop by to say hello and tell us they’ll be back later in the week (and seriously, this actually happens). So now we just have fun with our emails and don’t obsess over the performance metrics at all.

But how does this relate to you? Well, dear product person (potentially hiding behind your Product Marketing Manager), especially if you’re in a B2B situation, you’re likely dealing with similarly small, segmented customer lists and an email cadence that’s probably no more frequent than once a week. At that level of scale, something like A/B testing is likely going to give you very little statistical significance and you’re probably kidding yourself to think you’re finding any real insights. Instead, you’re better off focusing on building a good product, establishing a consistent tone/brand in your communications, and connecting with your customers on a human level.

Don’t worry about the direct ROI of every single email or test. As long as it’s not sucking up a disproportionate amount of your budget or resources, consider it an investment in an intangible asset – and tell your management that Deven said so. (Also, send them a link to this article so you can cover your butt!)

Facebook - Experimentation on a Different Planet

Let’s talk about Facebook’s iOS app. It’s been a while since I chatted with members on their iOS engineering team, but last time we spoke a few years back, the source code was already a staggering size. I’m talking 7 GB before it even gets compiled into a binary! I can only imagine it’s much larger now, with countless teams contributing code.

But the truly mind-blowing part is their testing infrastructure. I think it had something like 6,000 tests running constantly within the app? Performance tests, UX experiments, you name it. They’re tweaking everything, all the time.

Of course, they can do this because they have access to a third of the world’s population using their app. This works because of their insane scale, but it probably started working when they had just a few million users. They have entire teams dedicated to this kind of over-optimization, focusing on everything from increasing user conversion to boosting the percentage of chats using end-to-end encryption. And it’s not always directly about making more money; it’s about driving key company priorities - like making sure their users migrate to Threads.

You, dear PM, likely aren’t at Google, Meta or the like. Even if you are, you might not be on a Product that can tap that much user engagement within that company.

So if over-optimizing isn’t the holy grail for most people, what should you be doing?

Great Products Don’t Start with Math Experiments

It’s definitely not about blindly following personas, relying on gut feelings, or just building it and hoping they will come. There’s nuance, for sure, but it largely boils down to three key things:

Nail the Essentials (and Resist the Urge to Over-complicate): Focus on locking down the core functionality that your actual users are begging for. Then, resist the urge to mess with it too much. When we were building MGP to support the largest mapping and government customers on the planet, we were bombarded with requests from every direction. As one Sales Engineer yelled into my Teams chat (in ALL CAPS, naturally): “Make sure you have usable analytics!” Another well-meaning senior engineer chimed in: “I found three [not-so-big] customers who really want this one feature my team and I designed. Can we put it in there for launch?” But meanwhile, our 25 largest customers were unanimously screaming something to the tune of: “Can you just... find a f#$%ing reliable way to give me the data I want, when I want it, without making me create 5 different accounts or sign 3 contracts to do so?!” So that’s what we focused on: one single identity to access any content across all of Maxar, two client apps (one simple and one Pro-mode), open well-documented APIs to support streaming and downloading of ALL content types, and most importantly - everything finally under one contract vehicle the customer could actually sign.

Focus on 1-2 Financial Targets (and Ruthlessly Prioritize): Keep your eye laser-focused on the prize. What are the most important financial goals for your product? What are the metrics that truly matter? Everything else is just noise that will distract you and your team. I can’t go into too many specific details, but I can tell you that we had two big, overarching goals for the new platform at Maxar: First, Move all existing customers (and their existing revenue) to the new platform as quickly as humanly possible. Thankfully, there wasn’t too much friction here, internally or externally, once we built up some momentum. Second, Make sure we increased our overall book of business by XX% by offering a true value-add that would be universally recognizable by both our largest and smallest customers. That’s it. Everything we did was ruthlessly prioritized against those two goals. It helped us avoid chasing every new shiny thing. More importantly, establish trust with our customers and with our internal customer-facing teams (sales, customer success, reseller relations, technical support, etc.).

Match Simplicity (or Complexity) to Usage Patterns: Recognize how frequently your product is used and design accordingly. Don’t force simplicity where it hurts, and don’t overcomplicate where it’s unnecessary.Think about Excel. There are definitely times when you need customers to just come in, do something quickly, and get out. But what if you were trying to do really intricate macros, and the next software update made Excel look like Numbers?

Ignoring the oddities of AppleScript vs VBA, you’d probably blow your brains out and have your Microsoft account manager on the phone in 10 seconds. There are often times when a tool doesn’t need to look “clean and minimal,” and oversimplifying it actually hinders power users who rely on it on an hourly or daily basis. The workflows themselves need to be simple and efficient, but the tool itself might need to offer a rich set of features and options to support complex tasks.

Remember the People

Ultimately, the best product decisions aren’t always driven by data. While data is undoubtedly valuable, it’s just one piece of the puzzle. Sometimes, the most impactful decisions for a product come from empathy, intuition, and a deep understanding of your users’ needs. It’s about resisting the urge to over-optimize every tiny detail and instead focusing on the bigger picture: solving real problems for real people. So, take a moment to reflect on your own approach to product development. Is data guiding you, or is it clouding your view of the human element that truly drives product success? Are you so focused on optimizing the trees that you might be missing the forest?