Don't Build Fast without Building Right First

Originally published on May 16th, 2025

Stewed cooking is quite common across the world. In South Asia, it became prevalent because there was a lack of high-temperature cooking fuel, so cow dung, wood, or crude charcoal were the primary methods of making food. It’s a similar story in many other parts of the world, and that has shaped to quite a large degree what those cuisines tend to evolve into – dishes that require long, slow simmering to become tender and flavorful.

When your primary method to make large-scale batches of food is constrained by heating temperature, you have to extend the amount of time you do the cooking. This actually offers an excellent look into how product development differs in some really well-known products and services available in the market today.

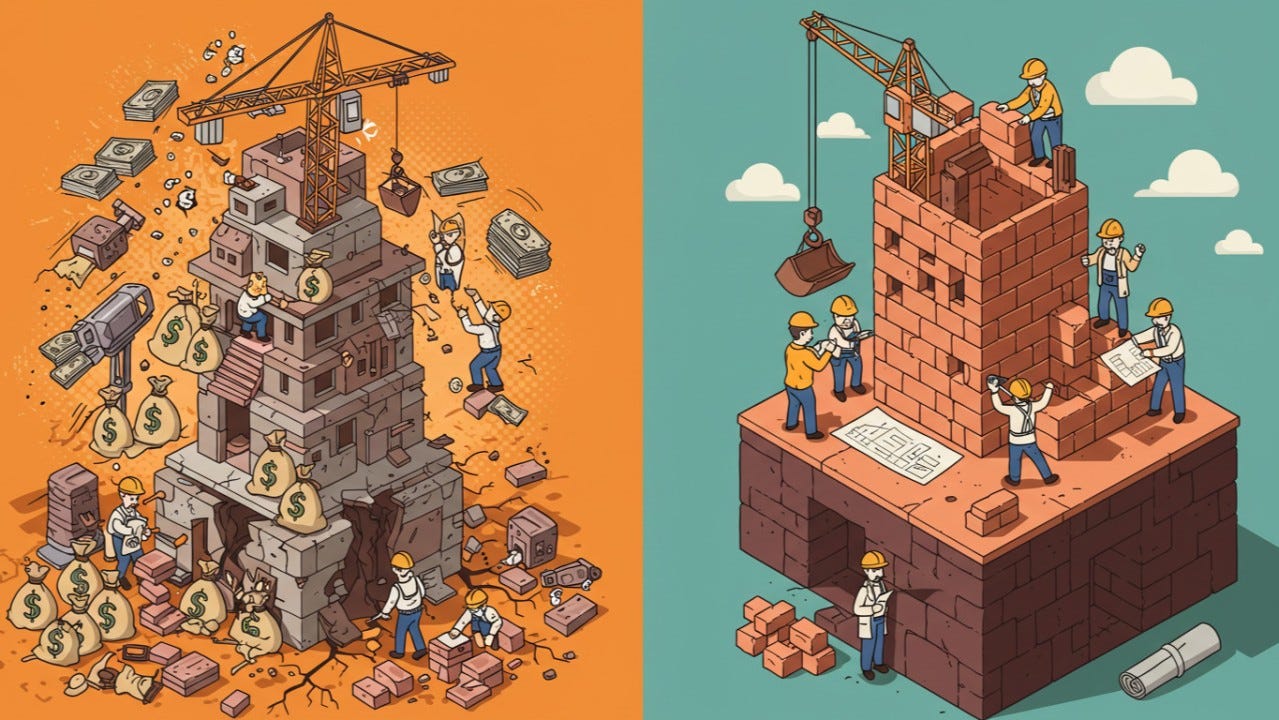

Think about it. When you have limited “heat” – limited capital, constrained resources – you have to take your time. You have to be disciplined, focus on the core, ensure every step is right before moving to the next. You build your flavor base slowly. But what happens when you suddenly get an artificial burst of high heat? An artificially large amount of capital injected into a business that hasn’t had time to simmer and develop its fundamental structure?

There’s an entire VC industry that developed with institutions juicing up businesses on the hope that growth and scale can magically solve underlying problems.

Companies that received this kind of premature, oversized capital often suffer through significant challenges in growth and gross retention of customers. There’s an entire VC industry that developed with institutions juicing up businesses on the hope that growth and scale can magically solve underlying problems. We could talk about the usual suspects like Uber or Doordash, which famously still lose money while squeezing customers and labor. But honestly, that story’s a bit tired.

Instead, I want to look at two specific examples from the peak startup boom era of the 2010s that illustrate this perfectly. One business got that huge, early capital injection and chased explosive growth before it was truly ready. The other took a more disciplined, focused approach. Their outcomes couldn’t be more different.

Back in the early 2010s, both companies emerged aiming at small and medium businesses (SMBs), promising to simplify HR. On the surface, they looked like similar disruptors. But their journeys, and their fates, highlight the difference between getting too much money before you’re ready to make that money work for you.

Let’s start with Zenefits. Founded in 2013, they were famously fueled by massive early capital – over half a billion dollars raised by mid-2015. They offered free HR software, making money instead by acting as the insurance Broker of Record for their customers. This meant they were deeply embedded in the complex, state-by-state world of insurance regulation from day one, but their focus was clearly elsewhere. With that massive funding, they chased hyper-growth on steroids. By mid-2015, just two years in, they’d hit just over $20M ARR, but had scaled to nearly 1,500 employees to make that revenue, and had a crazy $4.5 billion valuation. On the surface, they were cooking fast and were a huge darling in San Francisco. I worked a block away from their office and compared to the Macys.com office, their after work happy hours were awesome!

Too Much Funding, Not Enough Discipline

This growth outpaced fundamental operational and compliance things they needed to get right. Their culture became a high-pressure “growth at all costs” machine that a lot of us in tech already know about. Speed and sales targets consistently seemed to trump boring, but critical things like ensuring their brokers were properly licensed in every state.

This wasn’t just a few slip-ups; it was systemic. It led to predictable, severe problems: service issues surfaced as early as 2014-2015, massive compliance failures were exposed in 2016 (remember the CEO creating a browser extension to bypass mandatory training?), followed by regulatory fines across multiple states, leadership changes, significant layoffs, and ultimately, a forced fundamental shift in their business model to a paid subscription in 2017, long after the damage was done and trust eroded. Despite the massive early funding and explosive growth, Zenefits eventually sold to TriNet in 2022 for a figure significantly less than its peak valuation, effectively ending its run as an independent entity.

The Discipline Dividend: Why Gusto Won

Meanwhile, Gusto (originally ZenPayroll), started a bit earlier in 2011. While also well-funded (raising a pretty big seed round of $6.1 million), they approached growth differently. Their initial model was paid from the start, focused laser-like on one critical, complex area: payroll. They built a reputation for absolute accuracy and reliability – a non-negotiable foundation when you’re handling people’s paychecks and taxes.

Their growth felt more measured, more methodical. They built a culture that prioritized customer service and crucially, compliance right from the start, understanding the sensitivity and regulatory demands of payroll data. They didn’t chase hyper-growth at the expense of fundamentals. Only after establishing this solid core did they strategically expand into other HR areas like benefits (rebranding to Gusto in 2015), time tracking, and building strategic partnerships (like with accountants). Gusto reached a $1 billion valuation by December 2015 (a few months after Zenefits’ peak, showing a different trajectory), achieved profitability, and has continued to grow sustainably, reaching a valuation of $10 billion by 2021, remaining an independent and from the looks of it, a thriving company. They focused on building that strong foundation, mastering the simmer, and the result is a resilient, enduring business.

The contrast is stark and instructional for anyone building products or leading teams today. It shows what happens when one company gets a huge, early capital injection and chases explosive growth in a complex, regulated space without building the necessary operational, compliance, and cultural structures needed for that kind of heat. And what happens when another builds a solid core product, prioritizes discipline, accuracy, customer trust, and compliance from day one, allowing growth to happen more organically as the foundation strengthens.

The lesson here isn’t that funding is bad. But it’s pretty clear, chasing growth metrics without building a fundamentally sound, compliant, and customer-focused operation is like trying to serve a stew that looks done on the outside but is raw in the middle. It might impress briefly, but it won’t taste good and soon enough - it’ll get tossed out when no one is looking.